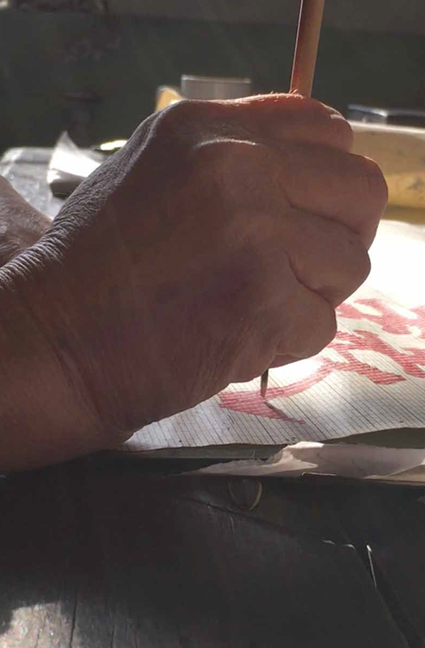

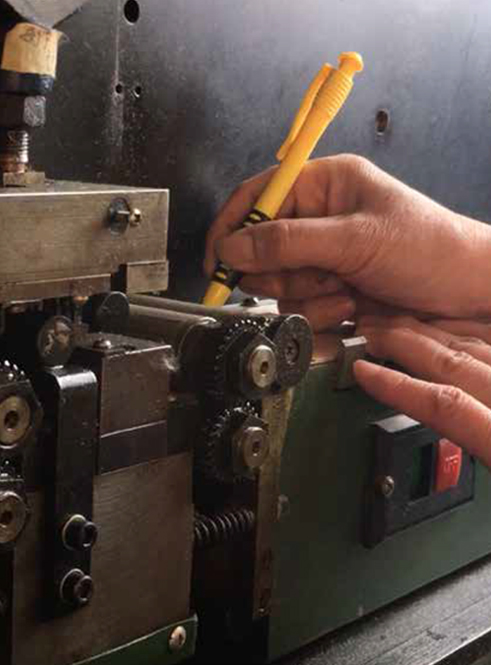

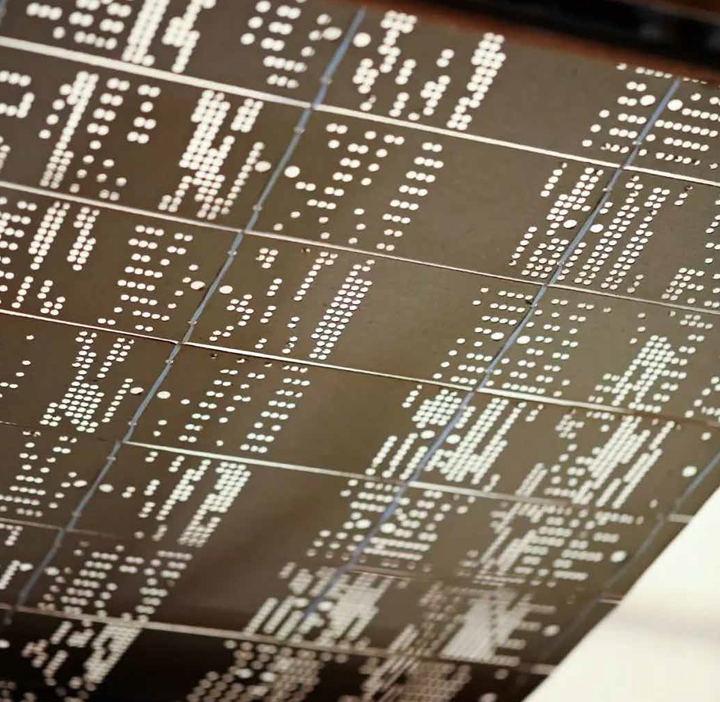

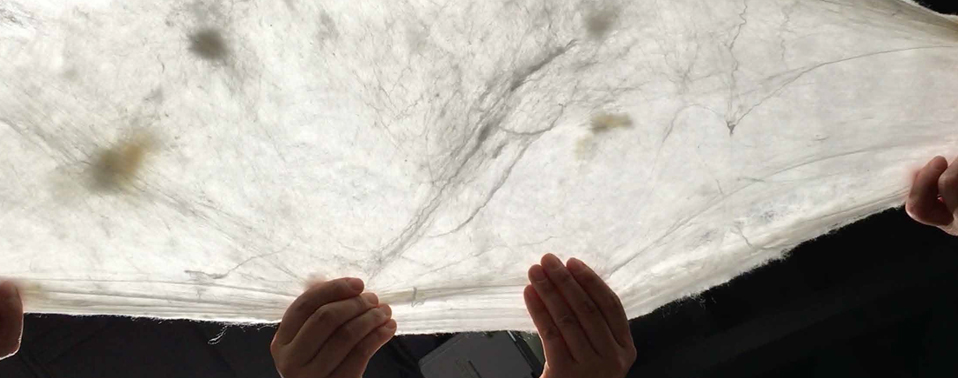

While ordinary quilts were still weaving the cycle of dawn and dusk through their warp and weft, the artisans of Lu Silk in 1969 were already etching stars onto 56,904 pattern cards—this was the silk epic of Chairman Mao Goes to Anyuan. Each frame of this masterpiece demanded six months of toil, swallowing the morning frost and night dew, to finally spin its splendor into being. These mulberry-paper cards, reminiscent of oracle bone inscriptions cast onto bronze vessels, yet also like a frozen fountain of time from movable type printing, built a rope bridge of civilization between the mechanical gears and the tender resilience of silk.